My research can be grouped into three broad strains. The first is the investigation of pre-modern Christian thought with an eye toward what it can tell us about the genealogical roots and unacknowledged deep structures of modern secular political thought. The second consists in expository and interpretive work on contemporary continental philosophy, including translation. The third comprises the interpretation of contemporary culture through television and film. Though I have pursued each strain on its own terms, I have increasingly found myself weaving all three together.

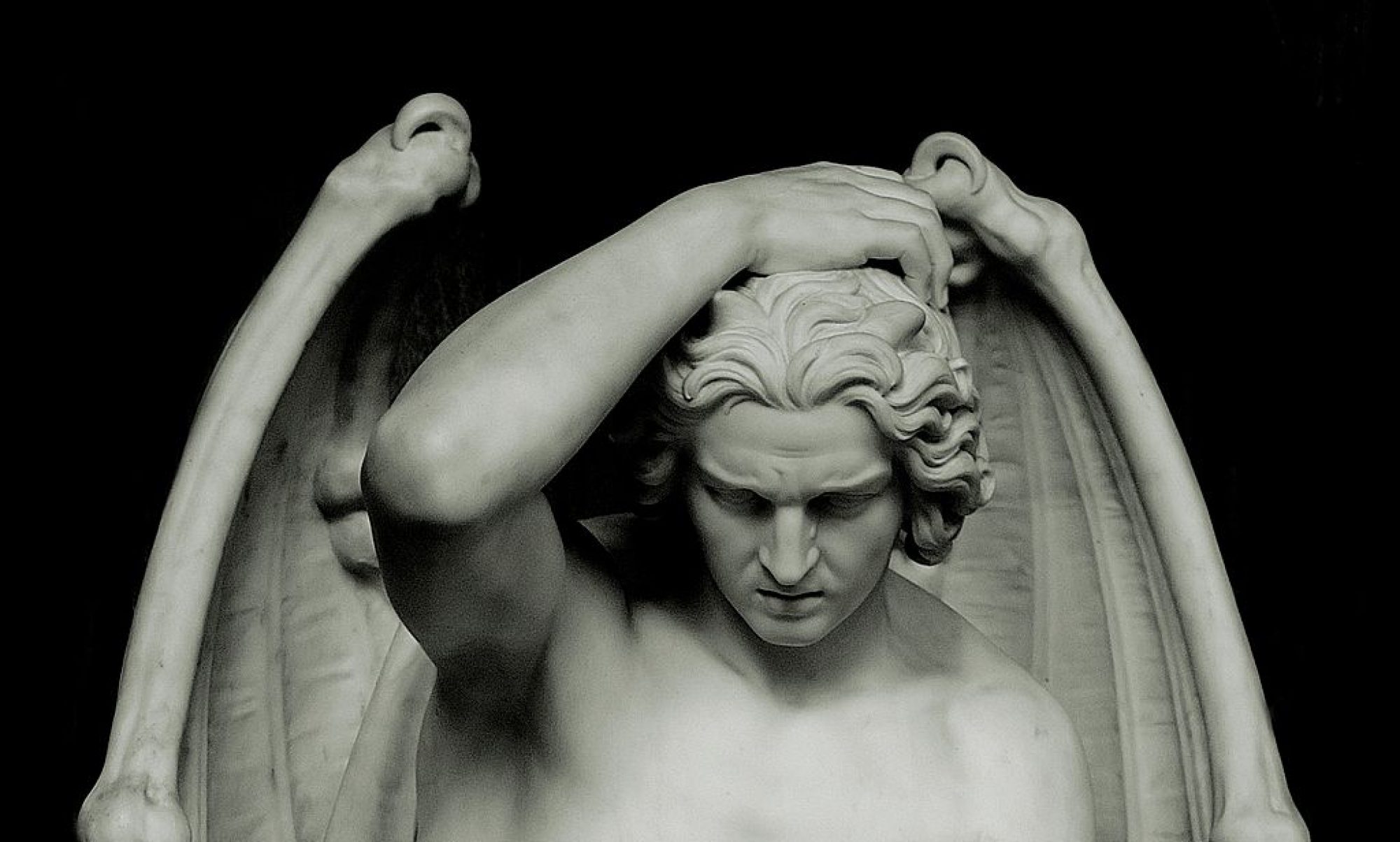

The research for my first major book belonged primarily in the first category. Published under the title Politics of Redemption: The Social Logic of Salvation (Continuum, 2010), this study looked at the various attempts throughout Western Christian history to answer the question—which is absolutely central and yet strangely lacks a definitive “orthodox” answer—of why Christ’s death and resurrection has any saving power for others. A surprising finding in my research was the central role of the devil in early salvation narratives, a role that was forcefully downplayed by later theologians. This sidelining of the devil corresponded with a major paradigm shift in the theory of salvation, and so I hypothesized that the devil might also serve as a kind of index or “canary in the coalmine” for other major shifts in Christian thought. That thesis guided the research that led to The Prince of This World (Stanford, 2016), where I use the devil’s shifting role as a way of tracing paradigm shifts on the question of how God governs the world more generally. In this history, the political and the theological are intimately interconnected, as the devil initially emerges as a symbol for oppressive earthly rulers and later, in an ironic reversal, comes to be associated with oppressed and marginalized populations within Christendom. Building on Schmitt’s concept of “political theology,” I was able to trace the sometimes unexpected roots of key modern concepts—such as the social contract, subjectivity, and racialization—to Christian theological discourse about the devil.

In both of my theological studies, I made extensive use of continental philosophy and theory. In Politics of Redemption, my approach was more eclectic and occasional, but by the time I came to write The Prince of This World, my use of these theoretical resources was much more focused and systematic. This reflects developments within my interpretive work on continental philosophy, which began in earnest with an introductory text on Žižek (Žižek and Theology, Continuum, 2008) and continued in the form of diverse essays on Žižek and other figures, appearing in popular venues like The Los Angeles Review of Books in addition to scholarly journals and anthologies. The rise of the philosopher Giorgio Agamben, who works extensively with Christian theological materials, provided an occasion for me to focus on my joint expertise in theology and philosophy. Especially crucial here was The Kingdom and the Glory, his massive study of the concept of divine governance, which was an indispensable point of reference for The Prince of This World but also a major object of critique. That critique comes only after considerable work understanding his project on its own terms, which took the form of translating several of his texts (ten volumes in total, published by both Stanford and the University of Chicago imprint Seagull Press), composing a series of essays, coordinating an edited volume on Agamben’s interlocutors, and ultimately publishing my own single-authored monograph on his intellectual development, Agamben’s Philosophical Trajectory (Edinburgh, 2020).

My translations of Agamben’s work reflect a deep interest in language and translation. I am able to work with texts in a variety of classical and modern European languages, including Attic Greek, Latin, French, German, and Italian. My translation work has primarily centered on Italian, but I recently expanded my published range with a translation of a previously untranslated essay by Nicole Loraux, a major French classical scholar who is among Agamben’s most important interlocutors in one of this recent books. In recent years, I have expanded my linguistic reach beyond the European sphere to include biblical Hebrew and classical Arabic. I am currently at work on an article comparing the political theology of the Qur’an with that found in the Pauline Epistles.

My interest in the genealogical roots of modern political concepts is paired with a fascination of contemporary reflections of those logics in popular culture. Upon completing my PhD (by which point I had already published my book on Žižek), I was eager to experiment with a different form of writing that had the potential to reach a broader audience. My first work in this vein was Awkwardness (Zero Books, 2010), which attempted to contextualize and interpret the rise of cringe-based “awkward” comedy in shows like The Office or Curb Your Enthusiasm. This project ultimately grew to become a trilogy investigating what our cultural fascination with other anti-social personality traits, such as the sociopathic detachment of anti-heroes like Tony Soprano (in Why We Love Sociopaths, Zero Books, 2012) or the creepiness of the Burger King mascot (in Creepiness, Zero Books 2016) can tell us about our social order. In all three works, I used the transition from the postwar Fordist paradigm to the contemporary neoliberal paradigm as my historical framework, arguing that all three of the anti-social traits studied reflect, in their own unique way, a social order that is slowly destroying its own sources of legitimacy.

This critique of neoliberalism, focused on its contemporary cultural manifestations, ultimately led me to my most influential work. Entitled Neoliberalism’s Demons (Stanford, 2018), it brings together my theoretical work on political theology and my genealogical work on Christian thought to argue that neoliberalism is a political-theological order that operates via the mechanism of demonization. Through a close reading of Christian narratives of the origin of the devil and his demonic hordes, I argue that God actually needs the devil to rebel and sets up a scenario where he is all but guaranteed to “freely” choose wrongly—yet still scapegoats the devil as morally blameworthy on the basis of the smallest sliver of free agency. The neoliberal discourse of choice operates similarly, as the social order grants us just enough agency to be to blame for social problems but not enough to actually fix them. I then use this political-theological perspective on neoliberalism to attempt to make sense of the right-wing reaction represented by Brexit and Trump.

My most recent publication on political theology is What is Theology? (Fordham University Press, 2021), an essay collection consisting of a mix of previously published, unpublished, and newly written material (with the latter representing over half the page count). In addition to showcasing the breadth of my research program, What is Theology? also represents a significant foray into questions of race. The final two essays in the collection, written in the midst of the George Floyd protests, connect modern racial thinking to the doctrines of original sin and divine providence, respectively, putting early Christian and medieval debates into dialogue with contemporary Black thinkers to think about the ways that modern ideas of race lead to a situation where members of certain groups are paradoxically treated as though their ancestry is a moral failing for which they somehow deserve to be punished.

Since that time, I have returned to the area of cultural criticism, writing a book-length manuscript on the Star Trek franchise that is currently in production at University of Minnesota Press. The work builds on an earlier scholarly essay comparing the fictional “canon” of the Star Trek universe to scriptural canons, which has emerged as a frequently cited point of reference for pop culture scholars. The book was solicited by prominent science fiction scholars Gerry Canavan and Benjamin Robertson to be one of the foundational volumes for their new series on “franchise studies,” which aims to investigate the unique opportunities and pitfalls of the sprawling fictional universes (such as Star Trek, Star Wars, Marvel, etc.) that dominate contemporary entertainment. Entitled Late Star Trek: The Final Frontier After the End of History, the book investigates the ways that Star Trek has tried and often failed to reinvent itself for new audiences in the 21st century. Drawing on my experience as an instructor in a Great Books program, I argue that there is no intrinsic reason why derivative works such as prequels and sequels have to be of low quality—after all, many of the greatest classics are sequels (e.g., The Odyssey, The Aeneid) or even prequels (i.e., derivative works set at a time prior to existing stories, such as Oedipus at Colonus or Paradise Lost). I claim that the problem with Star Trek (and, implicitly, other similarly large-scale storyworlds) is not that they are drawing on earlier stories or revisiting familiar tropes, but that corporate owners throw story development off course in a misguided attempt for ever-greater profits—a thesis that connects back to my earlier work on contemporary capitalist culture in Neoliberalism’s Demons.

Moving forward, I hope to continue on my primary research program on the political theology of the devil. My focus will be on Faust, whose infamous “deal with the devil” will allow me to continue to pursue the questions of free choice and moral responsibility while expanding my research to explore the ethical implications of modern science. Already in the earliest iterations of the Faust story, his demonic pact is tied up with his desire for illicit knowledge, a theme that Goethe will ultimately develop in his bold rearticulation of the legend. Drawing on Blumenberg’s account (in The Legitimacy of the Modern Age) of Christianity’s growing suspicion of intellectual curiosity up through the late Middle Ages and the challenge that posed to the development of modern science and inspired by Blumenberg’s treatment of Prometheus in Work on Myth (and Jared Hickman’s critical appropriation of that work in Black Prometheus; Oxford, 2016), I will position Faust as a kind of “hinge” figure for the transition from a theological to a scientific worldview. More specifically, I will argue that the negative valuation of intellectual curiosity was never fully overcome, as Faust (and Faust-like figures) are increasingly torn between individual happiness and a drive for knowledge that proves damaging to themselves and those around them. While Goethe will ultimately claim that the destructive side of knowledge can be redeemed, few other versions of Faust are as optimistic about the prospects for humanizing the drive to know.

This project will necessarily take me through the classic texts that directly adapt or evoke the legend of Faust, such as Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, Goethe’s Faust Parts 1 and 2, Mann’s Doctor Faustus, the operas of Gounod and Berlioz, and the films of Murnau and Szabó. In keeping with my growing interest in questions of race, and influenced by Hickman’s account of Black appropriations of the Prometheus myth, I will also seek out more indirect and non-literal engagements with the themes and tropes surrounding Faust among minoritized authors and artists—such as blues guitarist Robert Johnson’s supposed bargain with the devil or the moral temptations faced by the anonymous narrator of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. At the same time, I will treat the greater resonance of the legend among white European authors as evidence that Faust embodies modernity’s guilty conscience not only about the pursuit of scientific knowledge, but also about the ways that knowledge was deployed in the context of Western imperialism. I plan to conclude by relating the legacy of the Faust paradigm to the present situation of the Anthropocene, arguing that we need to develop new ethical models that are non-individualistic and orthogonal to questions of blame or forgiveness in order to confront our planetary dilemma.

(Updated September 10, 2024)